I have recently learned about medieval rabbit farming….I had no idea that rabbits were introduced by the Normans in the 11th century (hares are a native species) and that they were frail little creatures that didn’t survive in the English climate. I bought a Warrenhouse in Norwich to sort out a right of way issue over some family land, with the intention to re-sell it. The property had a totally inadequate kitchen and bathroom and the estate agents recommended getting permission to modernise before marketing it. The property is listed, largely due to distinctive leaded windows, so all changes need permission, which to those who have never done this is off-putting. One of the requirements is to produce a heritage statement to understand the significance of all aspects of the building and curtilage.

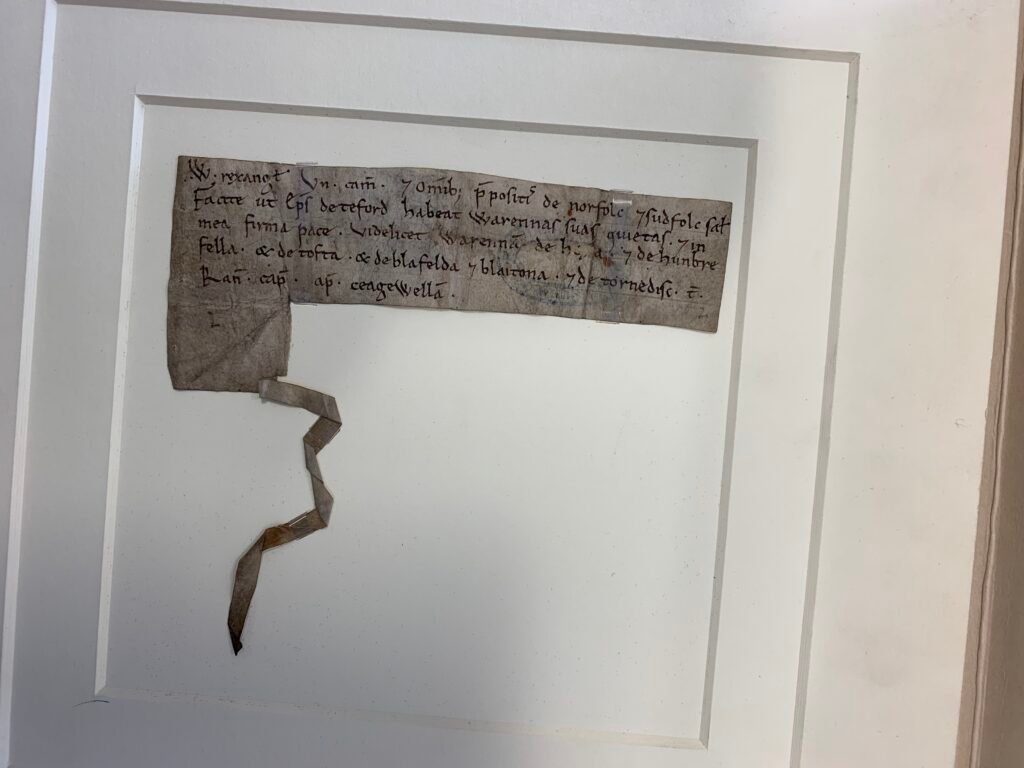

The right of warren, largely granted to the church and landed gentry, was to hunt small animals (ie not deer and boar) on common land. The son of William the Conqueror granted the right of warren to the Bishop of Thetford, who later encompassed Norwich as well, in 1090: I found the parchment (in Latin) giving this right in the Norfolk Archives. Warreners were originally in charge of hunting small game but when rabbits were introduced they took on the task of building pillow mounds for the rabbits to live in, complete with tunnels and earth on top to insulate the mounds and traps for the foxes! Warreners also kept dogs and ferrets to send into the mounds so they could catch the exiting rabbits in nets. Rabbits were highly valued for their fur and meat, especially by the clergy who weren’t allowed to eat red meat in Lent and rabbit was deemed a white meat.

Warreners tended to live in isolated houses in the middle of heathland, on their own. In fact in Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing, Claudio is referred to as being “as melancholy as a lodge in a warren”. As rabbits became hardier and other types of livestock were farmed, from about the 17th century, the need for a warrener declined and warren houses that still exist today are either ruins or unrecognisable as they have been extended and modernised into farmhouses. Warrenhouses were often of the same design, they had a large fortified room downstairs to store the valuable pelts and prepare the carcases with a spiral staircase in a corner to the upper room where the warrener lived, with fireplaces on both floors. The Norwich warrenhouse was near the city, and has been engulfed by Norwich, so it has been extended and altered and even built on the back of, but the original single room 2 storey building is still there with its very wide windowsills, bressamer (beam to support floorboards) and fireplaces. In East Anglia the garden growing the food for the warrener tended to be surrounded by high flint walls to keep the rabbits out.

The landed gentry and church raising rabbits on common land caused a lot of unrest and was in fact one of the reason behind peasants revolts, such as Ketts rebellion in Norwich. The revolts were against the enclosure of land but also the keeping of coneys (rabbits) which grazed the land intensively and meant reduced grazing for sheep, which were tended by wandering shepherds.

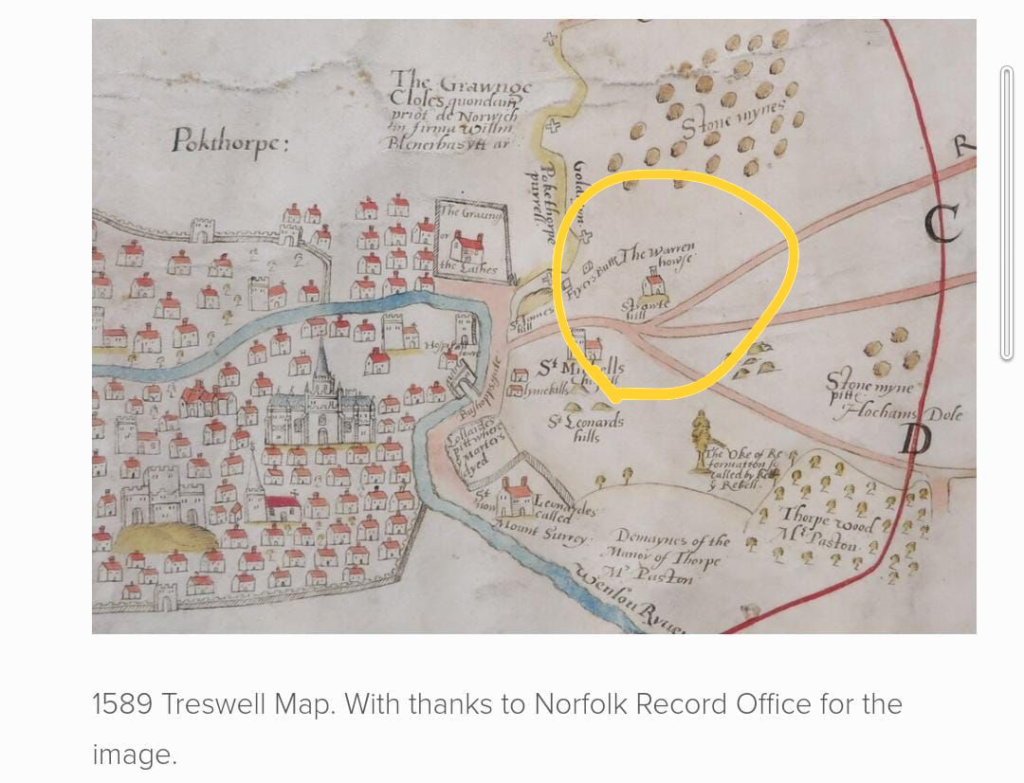

We have found out a lot about the history of the Warrenhouse but not yet when it was built! It is on a map of 1589 and on many subsequent ones, when it appears to change from being a house for the warrener to a hunting lodge. But we certainly have enough to understand which parts of the building need to be preserved and how to record its historic use, by for example reinstating lintels, or marking out in a different colour, in a modern floor where a wall has been removed.

Needless to say I have really enjoyed digging for evidence in the Norfolk Archives, finding an archivist that translated Latin scripts to me as if they were reading English and working with a conservation architect. In fact that bit of the story is inspirational. Fran is a good friend of mine. She qualified as a conservation architect, which is another stage further on from qualifying as an architect, and worked on making Sheffield cathedral accessible and many other heritage projects. But she gave it all up when she had children: she felt the whole profession was anti-women, even down to having to pay her annual qualification subscription to RIBA (needed to practice but you lost if you don’t pay to keep it going when you don’t work) when she was on maternity leave and also in South Africa with her husband where she didn’t have a work permit so only worked voluntarily as an architect. She had turned her hand to designing quilts (which she is rather good at), but I felt this project was right up her street so asked her to help me. She was magnificent and the work reminded her why she had chosen her original profession and how it could be so enjoyable. She was inspired to go back into the profession and got the first job she applied for as a senior heritage consultant, she is now just a few weeks in and delighted to be back. I am so very proud of her.

This may not be the sort of article you expected to find in Women in Food and Farming, but it is a bit about farming and bit about a woman…so I hope you have at least learned something. I have really enjoyed having the time to do this project. We are currently answering some questions from the planners but hope to hear soon that we have the permissions we wanted for a new kitchen, bathroom, shower and French windows onto a wonderful sunny garden.

Christine Tacon CBE, Founder WIFF, Chair MDS Ltd and Member Nominated Director Co-op Group